Binary star systems that contain a neutron star are important for probing fundamental theories of physics and for studying a large variety of astrophysical processes. For instance, the most energetic explosive phenomena seen in the cosmos, such as supernovae, kilonovae, gamma-ray bursts, gravitational wave mergers and fast radio bursts, often involve neutron stars in binary systems. Furthermore, they serve as an important testbed for Einstein’s General Relativity Theory, and binaries containing neutron stars are also excellent laboratories to study the behavior of cold ultra-dense matter. Finally, studying populations of binaries with neutron stars further allow us to several key processes of stellar evolution.

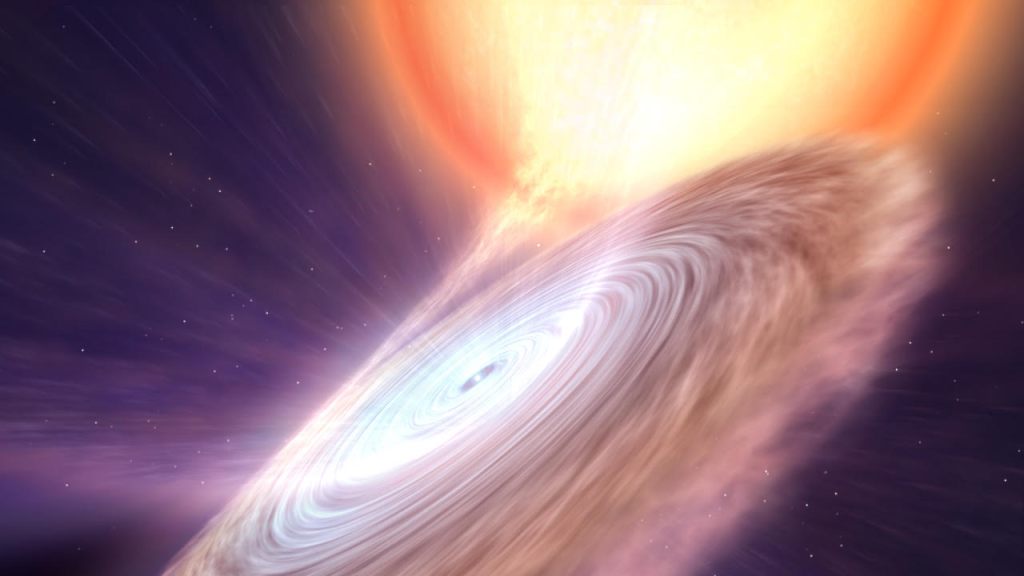

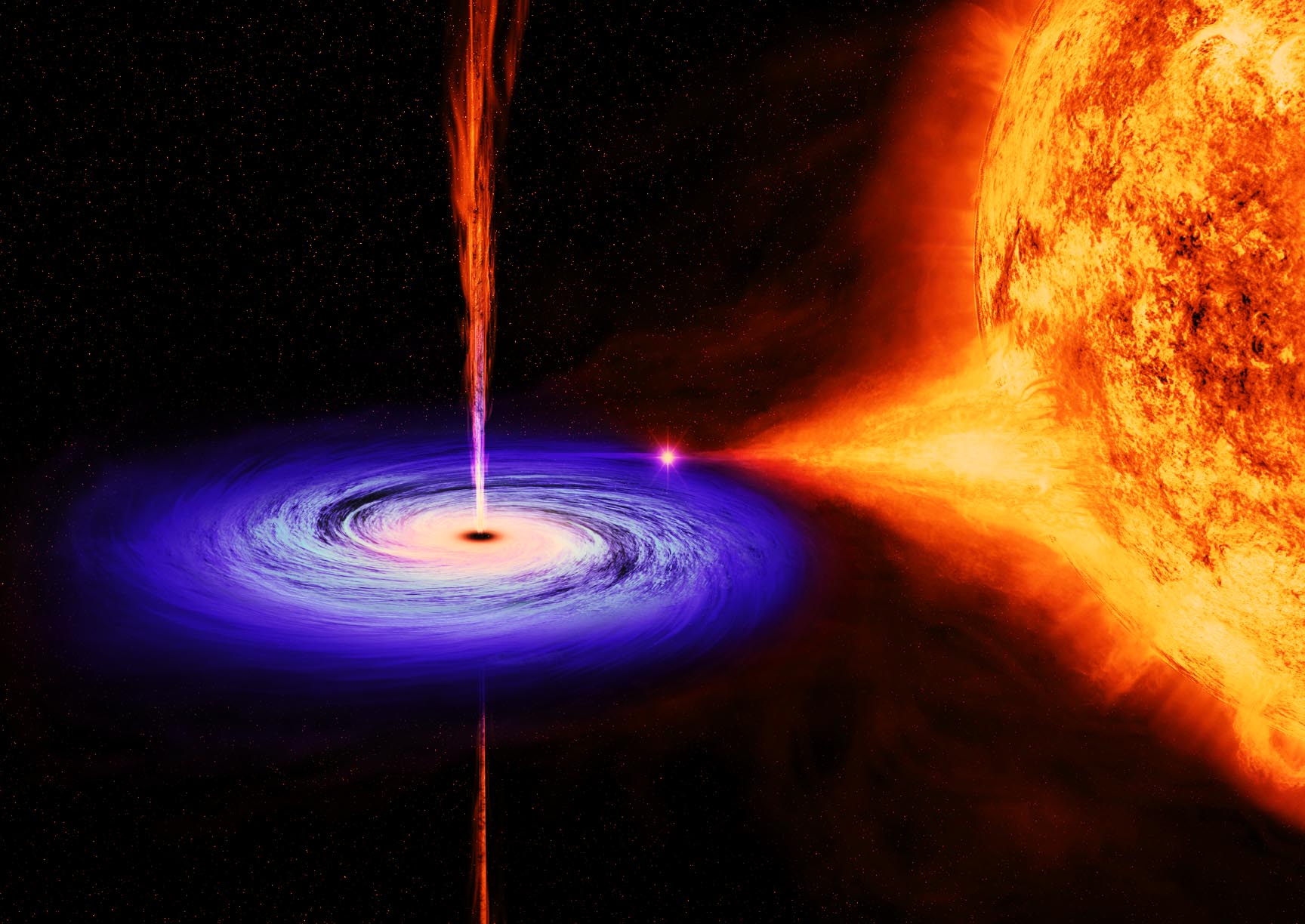

A particularly important phase in the life and evolution of neutron stars in binary systems is when the neutron star accretes mass from its companion star. This is when the system manifests itself as an X-ray binary. However, neutron stars do not only swallow gas, they also blow matter and energy back into space via outflows. These can be observed as highly collimated streams that are called jets and thought to be shot out with velocities of tens to hundreds of thousands of kilometers per second, or dense winds that have a larger opening angle and travel at lower speeds of a few hundreds to thousands of kilometers per second.

As in any astrophysical system where accretion takes place, outflows are ubiquitous among neutron star X-ray binaries. However, two key aspects of jets and winds are not understood yet: how these outflows are actually launched and how much mass can be lost from the binary in this way. Determining the mass loss is important, for instance, for understanding how long it will take for the neutron star to close in on its companion star and eventually collide with it, generating a burst of gravitational waves. The amount of mass contained in a wind is closely related to the mechanism that drive the wind.

Studies of X-ray binaries containing black holes have shown that disk winds are likely driven by thermal processes: X-rays produced in the inner parts of the accretion disk heat the outerparts of the disk, causing these to puff up. If the disk is large enough, the gas may at some point in the disk puff up to such an extent that it’s able to escape the gravitational pull of the black hole and flow away as a disk wind. Based on theoretical knowledge, it is expected that black hole X-ray binaries should have orbital periods of more than 8 hours to be able to have large enough disks to launch thermal winds. So far, this was consistent with observations, since disk winds have almost exclusively been detected in X-ray binaries with orbital periods exceeding 8 hours.

Analysing far-UV spectra of a very small neutron star X-ray binary called UW CrB, with the aim to understand the composition of its accretion disk, we surprisingly discovered features of a wind. Since the orbital period of this binary is only 2 hours, it should not be able to launch a thermal wind. Based on this observational discovery, we performed preliminary simulations and actually found that the X-rays emitted from the surface of the neutron star make it possible to drive a wind from smaller accretion disks than would be possible in black hole X-ray binaries (since black holes to have a surface where they can emit X-rays from). The wind in UW CrB does remain mysterious, since it was detected in only a fraction of the data that we analysed. This suggests that winds can potentially switch on and off on a time scale of hours, which was not previously known.

To establish the nature and time-variability of the wind in UW CrB, we have been granted time on several big observing facilities: the space satellites Hubble Space Telescope, XMM-Newton and Swift, as well as the optical/near-infrared Very Large Telescope (VLT, in Chile) and Grantecan (on La Palma). It was a huge challenge to figure out at what exact time all these telescopes could point to UW CrB at exactly the same time, but this ambitious and exciting observing campaign is happening in mid July. Stay tuned for the outcome!

Fijma, Castro-Segura, Degenaar, Knigge, Higginbottom, Hernandez Santisteban, Maccarone 2023, submitted to MNRAS: A transient ultraviolet outflow in the short-period X-ray binary UW CrB

Paper link: ADS

You must be logged in to post a comment.