Shedding light on an old black hole mystery using… a neutron star!

Neutron stars and black holes are both remnants of massive stars that ended their lives in a supernova explosion. They also both exert very strong gravity and when they are part of a binary star system, this allows them to devour gas from their unfortunate companion star. This gas spirals towards the cannibal forming a disk that is incredibly hot, so hot that it emits X-ray radiation. As these cosmic dinner parties can be spotted as sudden eruptions of X-ray emission, these stellar binaries containing a black hole or a neutron star are called X-ray binaries. However, neutron stars and black holes are greedy and cannot swallow all gas they attract; some of it is flung into space through powerful collimated jets or dense winds.

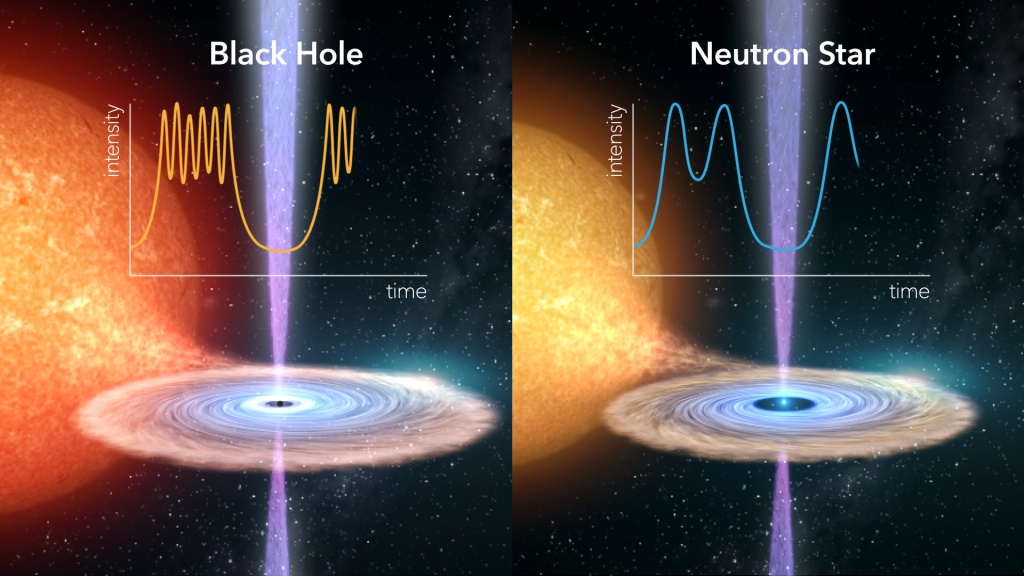

Despite their similar behavior, there is a distinct difference between the two tribes of cannibals: whereas for neutron stars the attracted gas plunges into their solid surface or anchored magnetic field where it may create observable shocks or explosions, a black hole silently swallows the gas from view beyond its event horizon. However, it has not been established yet how this and other differences between the two types of objects, such as the higher mass and faster spin rate of black holes, affect their eating patterns. Vice versa, comparing how neutron stars and black holes take their meals in can teach us how accretion and the production of outflows fundamentally works.

In 2018, a X-ray binary called Swift J1858.6-0814 was discovered when it suddenly started consuming material from its companion star. Unlike other X-ray binaries, it did so in an incredibly violent way, showing bright sparks, called flares, visible from radio to X-ray wavelengths The origin of this “cosmic fireworks” was unknown, but since it was so extreme, the astronomical community was convinced that this was the work of a black hole. However, over a year after its discovery, Swift J1858.6-0814 suddenly ignited a thermonuclear explosion, which require the presence of a solid surface. This exposed the black hole imposter, revealing that this extreme X-ray binary, in fact, harbored a neutron star.

Because of its extreme behavior, Swift J1858.6-0814 was closely watched, using many different space-based and ground based telescopes, including NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, ESO’s Very Large Telescope and ESA’s XMM-Newton satellite. For over a year, this suite of observing facilities was used to decipher the complex table matters of the neutron star. This led to the remarkable result that similar patters were found as seen in the notorious black hole X-ray binary GRS 1915+105, which had been standing out for decades because of its extreme behavior. Intense study suggests that the gaseous disk surrounding these compact objects must cyclically empty and fill, causing repeated spectacular ejections of matter into jets (seen at radio waves and infrared wavelengths). The discovery that both black holes and neutron stars experience this instability implies that it is a fundamental (i.e. unavoidable) process that occurs when compact objects are overfed.

Vincentelli et al. 2023, Nature 615, 45

Paper link: ADS

Artist’s impression of an X-ray binary containing a black hole (left) and a neutron star (right) swallowing gas from a companion star through an accretion disk. The insets show how the intensity of the emission varies strongly as the inner disk cyclically empties and re-fills. Whereas the timescales are different for the two objects, the underlying mechanism is thought to be the same. Image credit: Gabriel Pérez Díaz (IAC).

You must be logged in to post a comment.