Whenever a gigantic explosion occurs in the cosmos, or an astrophysical object guzzles up matter from its surroundings, so-called jets are shot out: collimated streams of plasma that hurdle through space at speeds of hundreds of thousands to billions of kilometers per hour. As jets carry enormous energy and travel very large distances, they may significantly impact their cosmic environment, for instance enriching it with exotic chemical elements or compressing gas clouds to the extent that these start to contract to form new stars. Moreover, a jet might carry away significant amounts of energy, mass and rotation, from the object that launches it hence changing its properties and evolution.

Despite their prominent role in shaping our universe, how jets are actually produced has puzzled astronomers for over a century, ever since the first recording of an astrophysical jet in 1918. The answer to this seemingly basic question is, however, essential to fully understand the wide impact of jets. This is because the launch mechanism determines the physical properties of the jet, such as its power, speed, and composition. For neutron stars, pressing questions are whether the star’s magnetic field is involved in launching jets and to what extent their jet production mechanism resembles that of black holes.

A rather unique neutron star to study the role of the stellar magnetic field on jet production is one with the stage name The Rapid Burster (formally called MXB 1730-335). It is thought for this neutron star there is a tug-of-war between its magnetic field, pushing gas outwards, and its accretion disk through which gas flows from its companion star flows towards it. During so-called Type-II X-ray bursts, flashes of bright X-ray emission that last seconds to minutes, the magnetic field is thought to be temporarily pushed inwards, allowing a sudden strong increase in the gas supply to the neutron star. Seeing if, and how, the radio jet responds to these Type-II bursts thus provides an excellent setting to study the role of the stellar magnetic field in launching jets.

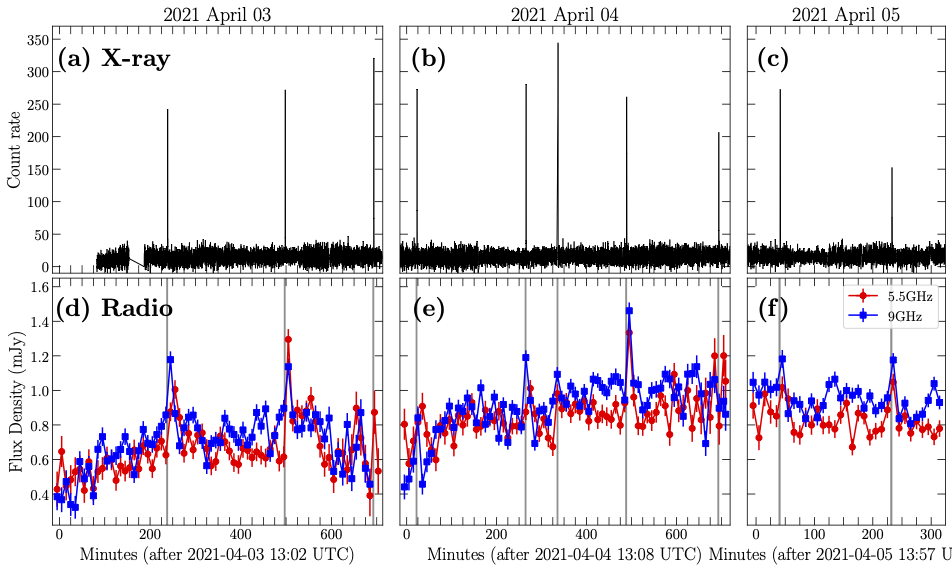

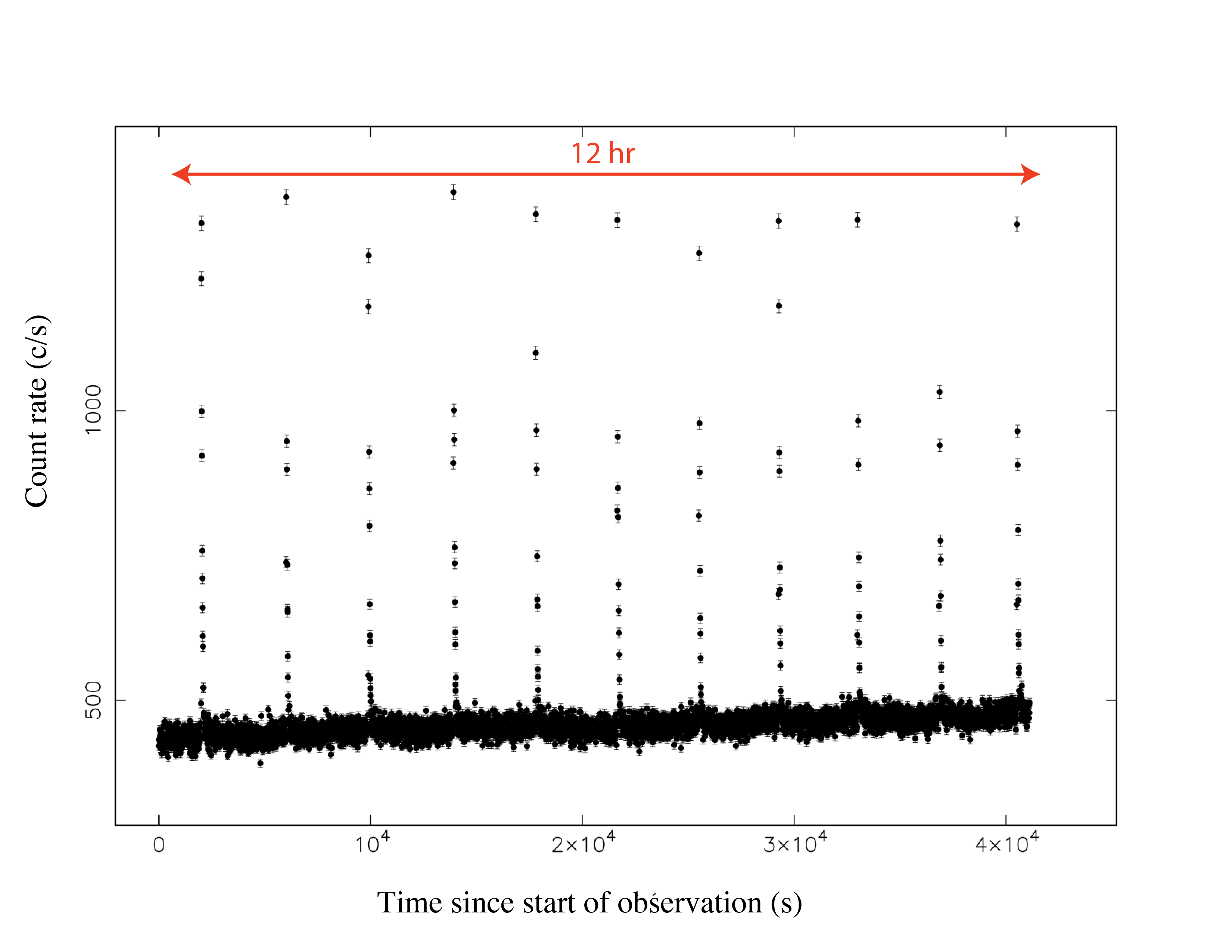

As with the thermonuclear burst / jet experiment, it was again an exciting challenge to design and execute the observing campaign to study the jet of the Rapid Burster. This is because this neutron star is dormant most of its time and only occasionally gobbles up gas from its companion star. Luckily, the Rapid Burster is a rare case where its meal times are rather regular, allowing to predict when a new episode of activity is about to occur. Making use of this, we devised a strategy that involved 4 different observatories. First, we monitored our target for signs of increased X-ray activity through the MAXI satellite, which is continuously scanning the sky in X-rays. When it detected the onset of a new accretion outburst, we started to monitor the source with the Swift satellite for accurate flux measurements and chart its X-ray bursts. As soon as Swift showed us that the Rapid Burster had become bright enough and had started showing type-II bursts, we initiated pre-arranged observations carried out simultaneously with the Very Large Array (radio) and Integral (X-rays).

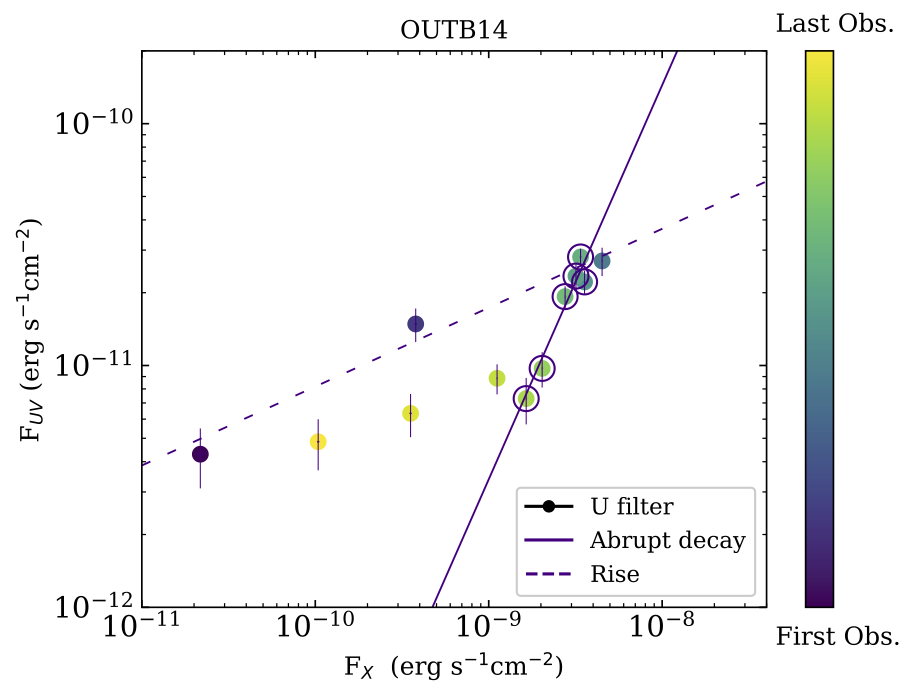

During our observing campaign, the Rapid Burster showed both short, rapidly recurring Type-II bursts, as well as a much longer one that was followed by a burst-free episode. Interestingly, we witnessed that the jet of the neutron star was solidly on when displaying the short bursts, but appeared to switch off after the longer Type-II burst. This could point towards a crucial role for the stellar magnetic field in launching jets, at least for this particular neutron star. Having conducted this successful pilot experiment, we can confirm this hypothesis by conducting a more extensive campaign to catch more longer Type-II bursts and study the associated jet response. Comparing these results a more systematic radio study of other neutron stars that do not display Type-II bursts will further allow to understand the role of the magnetic field.

van den Eijnden, Robins, Sharma, Sánchez-Fernández, Russell, Degenaar, Miller-Jones, Maccarone 2024, MNRAS 533, 756: The variable radio jet of the accreting neutron star the Rapid Burster

Paper link: ADS

You must be logged in to post a comment.