Studying the thermal evolution of neutron stars is a promising avenue to gain insight into their structure and composition, and therefore of how matter behaves under extreme physical conditions. These compact stellar remnants are born hot in supernova explosions, but quickly cool as their thermal energy is drained via neutrino emission from their dense interior and thermal photons radiated from their surface. When residing in low-mass X-ray binaries, neutron stars pull off and accrete the outer layers of a companion star. This can re-heat the neutron star and drastically impact its thermal evolution.

The accretion of matter causes a series of nuclear reactions (electron-captures and fusion of atomic nuclei) that produce heat at a rate that is proportional to the rate at which matter is falling onto the neutron star. These processes can significantly raise the temperature of the outer layers of the neutron star, the crust, which then become hotter than the stellar interior, the core. How much heat is released, and at which depth, depends sensitively on the structure and composition of the crustal layers. When the neutron star stops accreting (during so-called quiescent episodes), the crust cools down until it reaches the same temperature as the core again. How fast the crust cools depends strongly on its ability to store and transport heat, and hence on its structure and composition. Studying temperature changes of a neutron star due to accretion episodes thus holds valuable information about the properties of its crust.

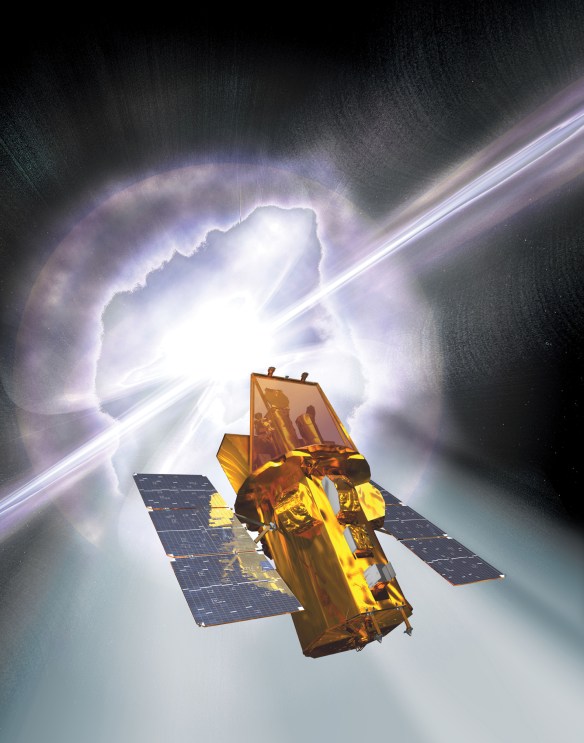

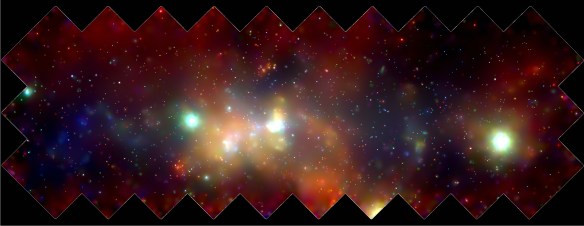

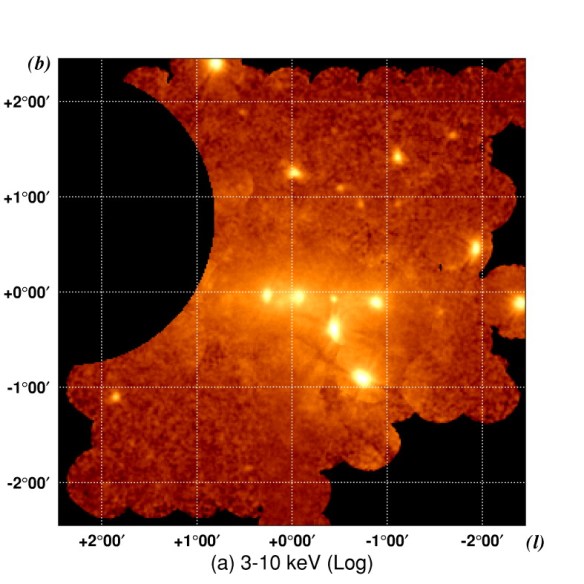

In 2010, a neutron star called IGR J17480-2446 started accreting matter from its companion star, temporarily making it the brightest X-ray source in the globular cluster Terzan 5. When it stopped 10 weeks later, we began to follow the neutron star every few months with the Chandra satellite to study any possible changes in its temperature. With our initial observations we discovered that the neutron star was about 300 000 degrees hotter than before it started accreting. This provided the first strong evidence that a neutron star can become significantly heated after just 2 months of accreting matter (rather than >1 year; read more here).

Since this neutron star was heated for a relatively short time, theory predicted that it should cool down rapidly. On the contrary, we have found that the neutron star is still considerably hotter than its pre-accretion temperature 2.5 years later! This indicates that there might be some important ingredients missing in our current understanding of heating and cooling of accreting neutron stars. To be able to distinguish between different possible explanations and hence fully grasp the implications of our findings of IGR J17480-2446, we aim to keep observing this neutron star until it has fully cooled. A new Chandra observation has been scheduled for this purpose in the next year (2014). We are anxious to find out how the temperature of the neutron star has changed by that time.

Degenaar, Wijnands, Brown et al. 2014, ApJ 775, 48: Continued Neutron Star Crust Cooling of the 11 Hz X-Ray Pulsar in Terzan 5: A Challenge to Heating and Cooling Models?

Paper link: ADS

You must be logged in to post a comment.