Some neutron stars that consume gas from a companion star generate much dimmer X-rays than the general population of X-ray binaries. Since the brightness scales with the amount of mass that is being devoured, it seems that in these sub-luminous X-ray binaries the neutron star is not eating much. There are two leading theories to explain why this may be happening, which breaks down to a supply or demand problem.

One obvious explanation might be that some neutron stars have old, small companion stars that are deprived of hydrogen (the most abundant element in the Universe) and supply only a limited amount of gas. Indeed, attempts to study the donor stars suggest that some of these neutron stars are being starved. However, there are also a few cases where the optical emission is bright and the transferred gas clearly contains hydrogen, implying that there shouldn’t be a supply problem.

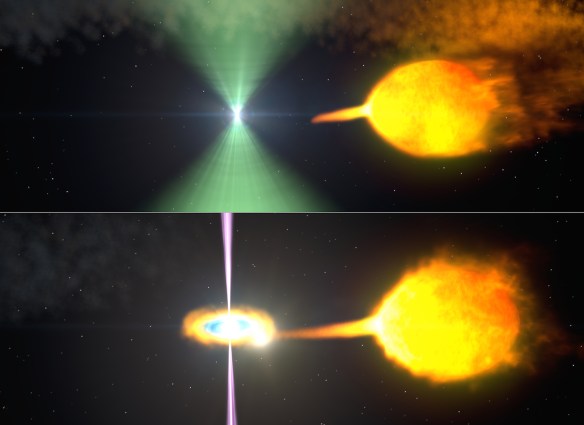

An alternative explanation is that some neutron stars have little appetite and consume only a small amount of the gas that is offered to them. In particular, these neutron stars may have a relatively strong magnetic fields that is able to stop the gas supplied by the donor from falling on to the neutron star or perhaps spit much of it out. To test this idea, we performed an in-depth study of the sub-luminous X-ray binary IGR J17062-6143.

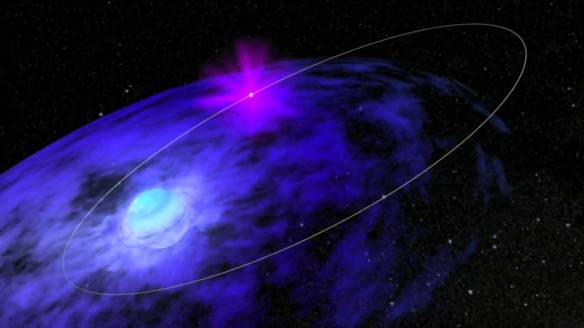

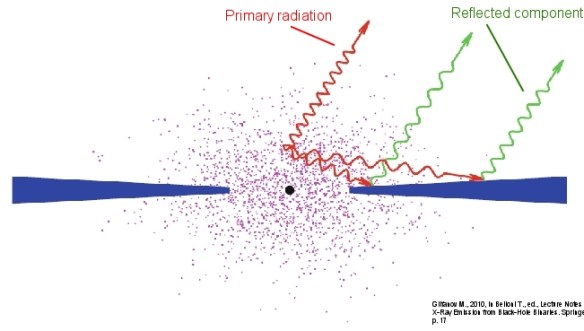

First, studying its X-ray reflection using the NuSTAR and Swift satellites, we found that the gas stripped from the donor star does not reach as close to the neutron star as normally the case in X-ray binaries. Second, using the Chandra satellite we found hints of narrow X-ray emission and absorption lines that could indicate that gas is blown away from the neutron star. The picture that appears to emerge from our study is that the neutron star in IGR J17062-6143 has a relatively strong magnetic field that pushes the in-falling gas away. Moreover, as the neutron star is (rapidly) rotating, its magnetic field may blow a large portion of the in-falling gas away, much like the propellor blades of a chopper do.

We are going to carry out further tests of this scenario. In particular, we recently obtained sensitive radio observations with the Australia Telescope Compact Array to search for additional evidence that this neutron star is spitting out a lot of gas. Moreover, we recently obtained an optical spectrum with the large (8-m diameter) Gemini South telescope in Chili, to test if this neutron star has a normal, hydrogen-containing companion star. We are eager to see what comes out of those new observations and if those allow us to conclusively solve the “supply or demand problem” for the neutron star in IGR J17062-6143.

Degenaar, Pinto, Miller et al. 2017, MNRAS 464, 398: An in-depth study of a neutron star accreting at low Eddington rate: on the possibility of a truncated disc and an outflow

Paper link: ADS

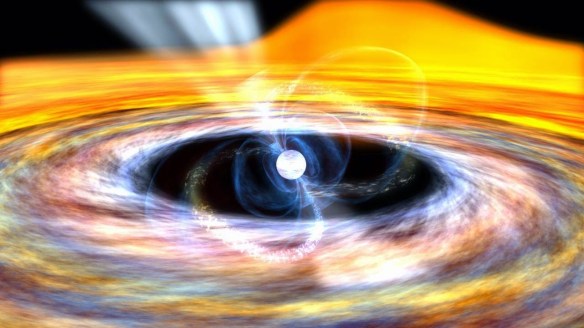

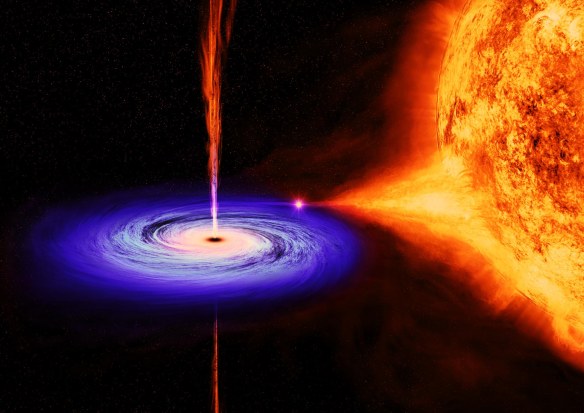

Artist impression of an X-ray binary with a neutron star that has a relatively strong magnetic field. Image credit: NASA.

You must be logged in to post a comment.