A new type of cosmic explosion discovered.

Staring up at the night sky, it may appear that the endless universe is calm and serene. However, the vastness of space harbors many extreme objects like black holes, neutron stars and white dwarfs. Despite being dead stars, their extreme properties causes them to produce all kinds of violent explosions like gravitational wave mergers, supernovae, gamma-ray bursts, X-ray bursts, fast radio bursts and what not. As of 2022, we can add a new type of explosion to this menagerie: the micronova.

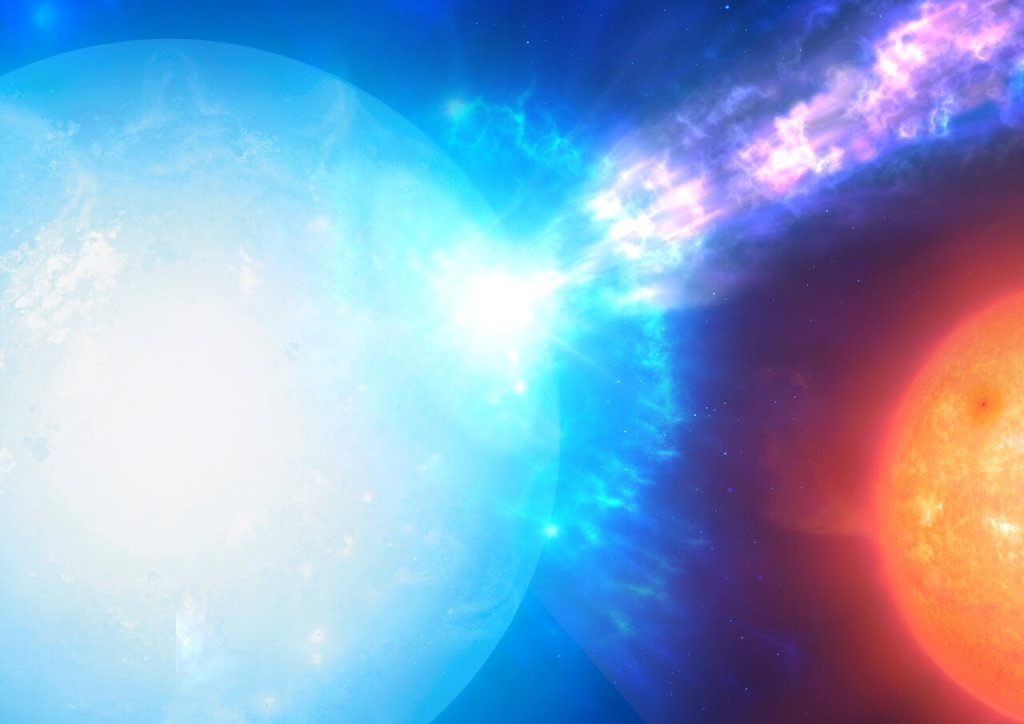

Micronova are thermonuclear explosions that occur on the surface of a white dwarf. In just a matter of hours, an amount of matter equivalent to 3.5 billion Great Pyramids of Giza is burned into flames. Despite being so magnificent, micronovae are just tiny explosions on astrophysical context. In particular, micronovae are about a million times smaller than the common nova explosions that have been known for many decades. Nova explosions occur when a white dwarf slurps gas from a nearby companion; when accumulating on the surface of the cannibal, this gas gets so enormously hot that hydrogen atoms explosively fuse together to form helium. The energy released in this process makes the entire surface of the white dwarf light up and shine bright for several weeks. This makes it easy to spot and study novae. Micronovae, however, are both shorter and less intense, which explains why they went undiscovered for so long.

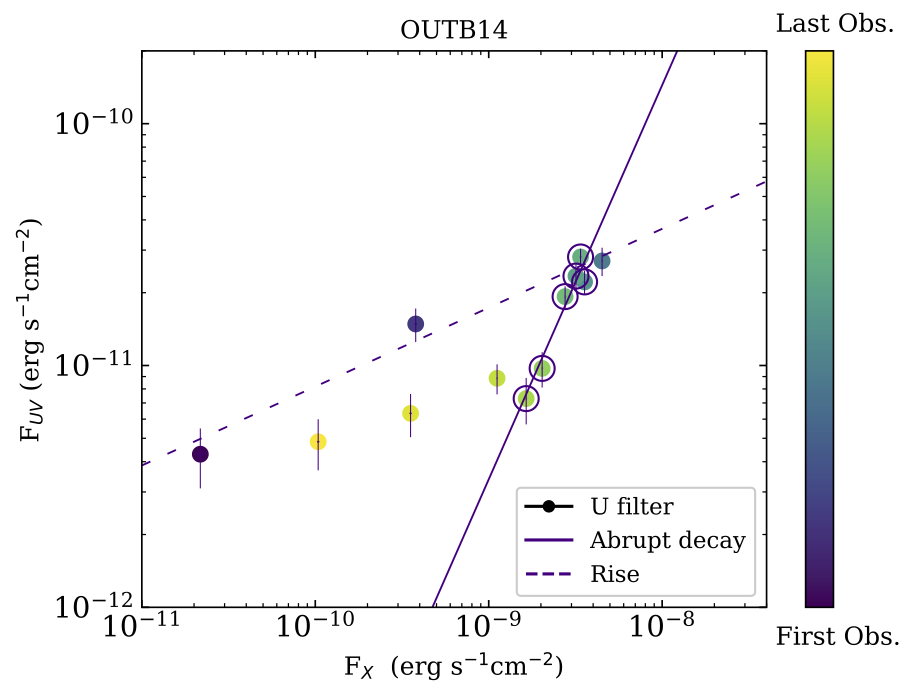

The mysterious micronovae were spotted in data collected with NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which takes highly frequent snapshots of large part of the sky. While designed to find new planets around other stars, its high-cadence optical monitoring can reveal many other interesting phenomena to the keen observer. It is in this way that a bright flash of optical light lasting for a few hours was found from a known white dwarf binary. Searching further revealed similar signals in two other systems. Their origin remained a puzzle until subsequent follow-up observations with ESO’s Very Large Telescope revealed a common denominator for the three binaries showing the hours-long optical flashes: all contained white dwarfs with magnetic fields strong enough to channel the siphoned gas onto the magnetic poles rather than it splashing over the entire surface. Putting things together and working out the energetics of the optical flashes revealed that these can be thermonuclear explosions that are confined to the magnetic poles, opposed to the well-known nova explosions that happen over the entire white dwarf surface. The smaller area involved in the explosion explains both the shorter duration and the lower energy output.

The discovery of micronovae shows for the first time that detonations apparently can happen in confined regions, which was not known before. The challenge is now to find more micronovae and to study them in detail to learn more about thermonuclear explosions on stellar cannibals.

Press release: ESO

Scaringi et al. 2022, Nature 604, 447: Localized thermonuclear bursts from accreting magnetic white dwarfs

Paper link: ADS

You must be logged in to post a comment.