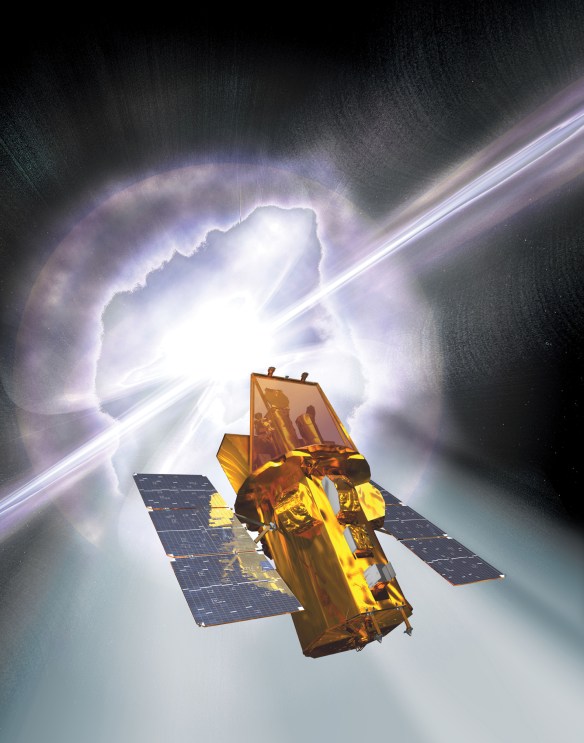

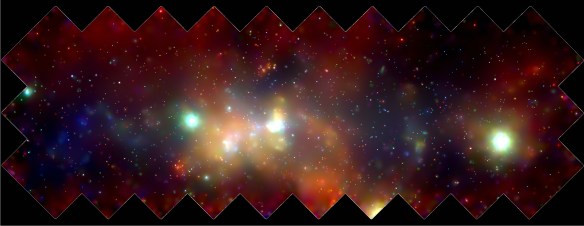

In 2006 February, shortly after its launch, the Swift satellite began monitoring the inner 50 x 50 pc (1.5×10^15 km squared) of our Milky Way with the on board X-Ray Telescope. In the months February-October*, 15-minute X-ray snapshots of our Galactic center were taken every 1-4 days. In nearly 10 years years time (2006 February till 2014 October), this accumulated to nearly 1.3 Ms of total exposure time, equivalent to about 15 days of continuous observing. This legacy program has yielded a wealth of information about the long-term X-ray behavior of the Milky Way’s supermassive black hole Sgr A*, as well as numerous transient X-ray sources that are located in region covered by the campaign.

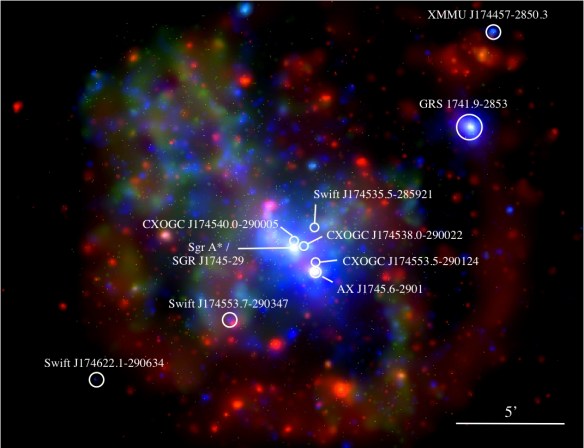

One of the main discoveries resulting from this campaign was the detection of six bright X-ray flares from Sgr A*. These are mysterious flashes of X-ray emission during which the supermassive black hole brightens by a factor of up to approximately 150 for tens of minutes to hours. Unfortunately, Swift temporarily lost its view of Sgr A* as of April 2013, due to the sudden awakening of a nearby ultra-magnetized neutron star (a “magnetar”). The X-ray emission from this object was about 200 times brighter than that of Sgr A*, hence it outshined our supermassive black hole. However, the notorious magnetar steadily faded over time and in late 2014 we regained view of the supermassive black hole again. Indeed, a seventh X-ray flare from Sgr A* was caught in 2014 September, the brightest ever seen with Swift.

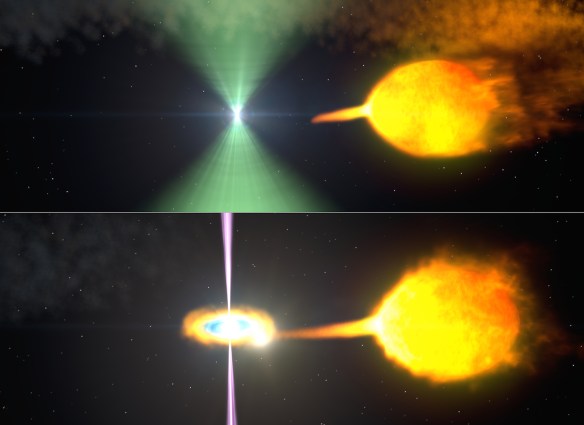

The Swift/XRT monitoring campaign has also been instrumental to understand the nature of a peculiar class of sub-luminous X-ray binaries. These are binary star systems in which a neutron star or a black hole accretes matter from a nearby companion (e.g., Sun-like) star. It has been a puzzle for decades why a small sub-group X-ray binaries are much fainter than accretion theory prescribes. This suggests that these neutron stars/black holes have little appetite, but the question is why. Swift has made a very important contribution in mapping the accretion behavior (“eating patterns”) of this class of objects and also identified 3 new members.

In addition, we discovered that “normal” X-ray binaries (i.e., ones eating more exorbitantly) sometimes display similar eating patterns as the sub-luminous X-ray binaries, giving important clues about the underlying mechanism producing low-level accretion events (i.e., fasting periods). For example, we found that in some cases the neutron stars/black holes sub-luminous X-ray binaries were likely caught enjoying an occasional midnight snack, and should be feasting on a larger banquet at other times. However, the behavior of one particular neutron star suggests that it may have a relatively strong magnetic field that sometimes simply impedes the infall (i.e., accretion) of material that is transferred from its companion. This object is therefore a candidate X-ray binary/millisecond radio pulsar transitional object.

After nearly 10 successful years, continuation of Swift’s Galactic center monitoring program remains highly valuable. For example, this would allow the collection of even more X-ray flares from our supermassive black hole, and to investigate whether the eating patterns of Sgr A* change in any way after the gaseous object “G2” has swung by.

Degenaar, Wijnands, Miller, Reynolds, Kennea, Gehrels 2015, JHEA 7, 137: The Swift X-ray monitoring campaign of the center of the Milky Way

Paper link: ADS

Swift/XRT monitoring campaign website: www.swift-sgra.com

*Due to proximity of the Sun the center of our Galaxy cannot be observed with Swift in November-January.

You must be logged in to post a comment.